Dr. Inyang Uwak

Research and Policy Director

As winter approached, we feared another storm. On January 14th, 2024 temperatures dropped to below freezing. There were signs everywhere to protect your people, plants, pipes, and pets. Over the next couple of days, there were calls from ERCOT to power down to prevent overloading the grid.

Walking in the morning, hoping to enjoy the crisp air, was nearly impossible because the air was heavy with an unexplainable smell. Driving across town, we saw the flares.

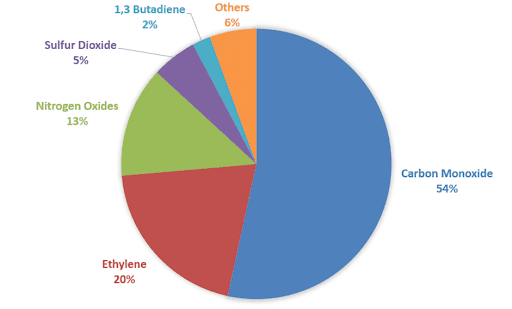

Petrochemical industries flare excessively during weather events due to a Start-up, Shutdown Malfunction (SSM) event. When industries are not adequately prepared for these weather events, they release tons of harmful pollutants into the environment of fenceline and downwind communities. This year, Carbon monoxide accounted for the largest share of the emissions, at 53.4% of the total (nearly 250,000 lbs.).

The top 5 emitted pollutants constituted 94.3% of the 465,185.7 pounds of pollution released into the air.

These flaring events also involved permit violations. Of the 11 total emission events across all facilities, 5 emitted a pollutant over its permitted limit at least once, with most emission events registering multiple exceedances. Therefore, 18 permit limit exceedances (or permit violations) occurred across all facilities, with Lyondell Chemical’s Bayport Choate Plant recording the most (12).

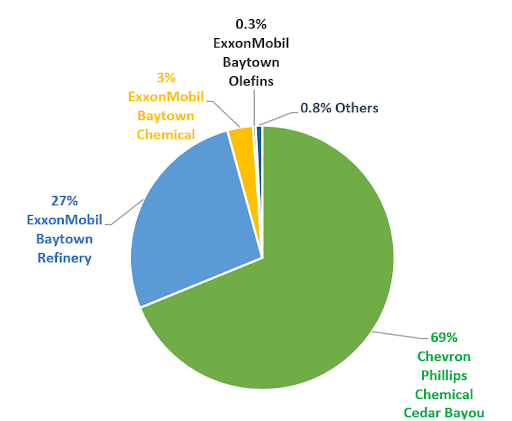

Who was emitting all these compounds? It came down to Chevron Phillips, and ExxonMobil. Cumulative emission totals for each facility across emission events from the 14th of January through the 17th of January ranged from:

- Chevron Phillips Chemical Cedar Bayou Plant: 320,789 lbs.

- ExxonMobil Baytown Refinery: 125,399.3 lbs.

- ExxonMobil Chemical Baytown Chemical Plant: 14,676.5 lbs.

- ExxonMobil Chemical Baytown Olefins Plant: 1,495.1 lbs.

- Others: 3,722.86 lbs.

What can we do about it?

We can start with a policy change. During Startup Shutdown Malfunction (SSM) events, industrial and power plant polluters can release more harmful air pollution during a single pollution spike than legally allowed in an entire year without consequences or reporting requirements. If these loopholes exist, fenceline and downwind communities can be exposed to excess toxic chemicals.

The Environmental Protection Agency is reassessing inadequacies in Texas’ handling of these SSM emission events. We are currently waiting on a decision from the EPA to hopefully expand the protections for air quality under the Clean Air Act, including enforcement tools like fines and requesting more comprehensive reporting from facilities.

For community members, if you see or smell something, say something. Report a smell or an emission event (like dark smoke at a flare) to the relevant authorities. This can include photos, videos or writing.

In the meantime, industrial facilities should take steps to prevent the need for flaring in the first place by adopting efficient emergency preparedness plans, including developing an efficient Risk Management Plan (RMP), weatherizing their facilities, upgrading aging equipment and technology, and improving extreme weather resilience and backup power sources to prevent flaring.

Fenceline communities deserve transparency from facilities as their health is affected by their pollution, because everyone has a right to breathe clean air.